Apocryphicity

A Blog Devoted to the Study of Christian Apocrypha

Apocryphicity

A Blog Devoted to the Study of Christian Apocrypha

Philip Jenkins, author of Hidden Gospels: How the Search for Jesus Lost Its Way (2001), has posted a series of articles on Robert Graves’ 1946 novel King Jesus in anticipation of his latest book The Many Faces of Christ:The Thousand-Year Story of the Survival and Influence of the Lost Gospels, due in October from Basic Books. The connection between Graves’ novel and the Christian Apocrypha is summed up as: “Obvious flaws apart, so much of King Jesus is fascinating, not least in terms of the alternative theories about Jesus and early Christianity that Graves presents. So many of these, moreover, are familiar to us today in the form of supposedly astonishing discoveries from recently found Gnostic gospels. Reading King Jesus, though, we see that these ideas were standard components of a 1940s bestseller, written the year before the celebrated finds at Nag Hammadi (and two years before the Dead Sea Scrolls were found).” Jenkins began discussing the novel in a post on Aletia, “Rediscovering King Jesus,” and then in three posts on Patheos (“King Jesus,” “Jesus the Essene,” and “Jesus, Ebionites and Jewish Christians”). Here is the abstract for The Many Faces of Christ:

The standard account of early Christianity tells us that the first centuries after Jesus’ death witnessed an efflorescence of Christian sects, each with its own gospel. We are taught that these alternative scriptures, which represented intoxicating, daring, and often bizarre ideas, were suppressed in the fourth and …

The standard account of early Christianity tells us that the first centuries after Jesus’ death witnessed an efflorescence of Christian sects, each with its own gospel. We are taught that these alternative scriptures, which represented intoxicating, daring, and often bizarre ideas, were suppressed in the fourth and …

The latest issue of the Journal of Biblical Literature features an article by Annette Yoshiko Reed entitled “Afterlives of New Testament Apocrypha” (JBL 134.2 [2015]:401-25). Readers of Apocryphicity may remember that Annette presented this paper as the keynote address of the 2013 York University Christian Apocrypha Symposium. Annette decided shortly after the event not to include the paper in the proceedings, in part because we would not be able to include all of the papers in the volume and also because it was not intended to be a formal paper. The publication of the proceedings have been somewhat delayed, so much that Annette has found the time in the interim to work up the keynote into publishable form. I’m glad to see that the paper will find a wider audience after all. As for the proceedings, they should be available by the time of the 2015 Symposium in September. Here is the abstract of Annette’s paper:

This essay explores the place of parabiblical literature in biblical studies through a focus on New Testament apocrypha. Countering the assumption that the significance of this literature pivots on its value for understanding the origins of Christianity, this essay calls for fresh attention to the afterlives of these writings. The first section traces the genealogy of the notion of the NT apocrypha as countercanon, as well as the history of the debate over whether “apocrypha” preserve secret or suppressed truths about Jesus and his earliest followers. It points to the influence of post-Reformation …

The long-in-development essay collection Rediscovering the Apocryphal Continent: New Perspectives on Early Christian and Late Antique Apocryphal Texts and Traditions (edited by Pierluigi Piovanelli, Tony Burke, with Timothy Pettipiece; WUNT 1/349; Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2015) is now available. The book collects essays from the 2004-2006 SBL Christian Apocrypha sessions and the 2006 Ottawa International workshop (“Christian Apocryphal Texts for the New Millennium: Achievements, Prospects, and Challenges”) hosted by Pierluigi Piovanelli. I was asked by Pierluigi back in September 2013 to help finish the editing of the materials and it is gratifying to see them in print at last. For more information, see the Mohr Siebeck catalog entry, much of which is excerpted below.

___________________

This volume collects the contributions of a group of North American scholars who started rethinking, in 2004, the traditional category of New Testament Apocrypha, largely dominated by theological concerns, according to the new perspectives of a greater continuity not only between Second Temple Jewish and early Christian scriptural productions, but also between early Christian and late antique apocryphal literatures. This is the result of the confluence of two, so far, alternative approaches: on the one hand, the deconstruction of the customary categories, inherited from ancient heresiology, of “Jewish Christianity” and “Gnosticism,” and on the other hand, the new awareness that the production of new apocryphal texts did not cease at the end of the third century but continued well into late antiquity and beyond. These papers bring together for the first time the …

Though titled “Modern Gnosticism,” the final lecture for my Gnosticism class covered more than the past century. We examined medieval forms of Christian Gnosticism, as well as Jewish and Islamic analogues, and some expressions of Gnosticism in modern literature, including Philip K. Dick and, well, Harry Potter. Our course textbook, Nicola Denzey Lewis’ Introduction to “Gnosticism,” does not cover this material, so I had students prepare for the class by reading Richard Smith’s essay, “The Modern Relevance of Gnosticism,” featured as an appendix to James Robinson’s The Nag Hammadi Library collection.

We began with an overview of gnostic groups who came into existence after the demise of the Manicheans, tracing a path from the Paulicians, an Armenian sect operating from the 7th to the 10th centuries that combined aspects of Manicheism and Marcionism, through the Bogomils active in Bulgaria and Bosnia-Herzogovina from the 10th to the 12th centuries, to the Cathars in France and Italy from the 12th to the 13th. For the Cathars we looked at the circumstances of their origin and their eradication in a Crusade called by Pope Innocent III. When asked what to do with the inhabitants of the town of Beziers when it became apparent it would be difficult to distinguish faithful Catholics from Cathars, Innocent famously said “Kill them all. God will know his own”—words remembered even today when someone says, “Kill ‘em all. Let God sort ‘em out.”

But that was not the end of Gnosticism. The Renaissance and the Enlightenment brought challenges …

Thanks to CNN’s Finding Jesus I was able to sit back and relax a bit this week and let the episodes on the Gospel of Judas and Mary Magdalene do much of the work for me. We began our look at Judas with an overview of his appearances in the canonical gospels, covering some aspects of Judas’ story not mentioned in the documentary, including the additional story about his demise from Acts 1:18-20 (it seems most documentary and filmmakers prefer the story of Judas’ repentant suicide to the one of his fall and bowels-gushing). I couldn’t resist also adding the third story of Judas’ death recounted by Papias of Hierapolis and a brief mention of two other Judas apocrypha: the Latin Life of Judas and the Legend of the Thirty Pieces of Silver. Then we looked at the well-loved scene from the Last Temptation of Christ where Jesus tells Judas that he has to betray him; Judas asks him, “Would you be able to betray your master?” Jesus replies, “No, that’s why I was given the easy job.”

I provided the students with a summary of the major acts in the drama behind the publication of the Gospel of Judas. I touched on a few of them that intersected with my own knowledge of the text (having access to Charlie Hedrick’s initial translation, hearing Louis Painchaud’s paper at the Ottawa Christian Apocrypha workshop). When it came time to mention National Geographic’s publication of the text, I showed them …

The final episode of CNN’s Finding Jesus: Faith, Fact, Forgery looked at the role of Mary Magdalene in the life of Jesus. The relationship between the two is probably the most burning issue in contemporary popular discourse about Jesus; most recently, the topic has been brought o public attention via the so-called Gospel of Jesus’ Wife and Simcha Jacobovici and Barrie Wilson’s controversial book The Lost Gospel—neither of which, with good reason, were discussed in the documentary. But viewers did learn about three other apocryphal texts: the Gospel of Thomas, the Gospel of Philip, and the Gospel of Mary.

But first, what does the documentary say about canonical references to Mary Magdalene? They begin with Luke’s version of the story of the woman who anoints Jesus (Luke 7:36-50). Luke sets the story in the house of a Pharisee named Simon. There “a woman of the city, who was a sinner” anoints the feet of Jesus with ointment contained in an alabaster jar. The Pharisee says to himself (not aloud), “If this man were a prophet, he would have known who and what kind of woman this is who is touching him—that she is a sinner.” Traditionally, at least from the time of Pope Gregory, this woman has been identified (or better: conflated) with Mary of Magdalene, who appears immediately after this story in Luke’s description of women who “provide for [Jesus and the twelve] out of their resources” (8:3). Mary is further described as someone “from …

Much of our Gnosticism course to date has focused on western forms of gnosis (well, more westerly, I suppose), but this week we moved east for a look at Manicheism, Mandaeism, and Hermeticism. We were flying without a net for much of the discussion, as Nicola Denzey Lewis’ textbook has a chapter on the Nag Hammadi Hermetic texts but nothing on the Manicheism and Mandaeism. As I have said before, the textbook is self-consciously an introduction to the Nag Hammadi library and strays little from that corpus; the only exception is a chapter on the Gospels of Judas and Mary, which we will turn to next week.

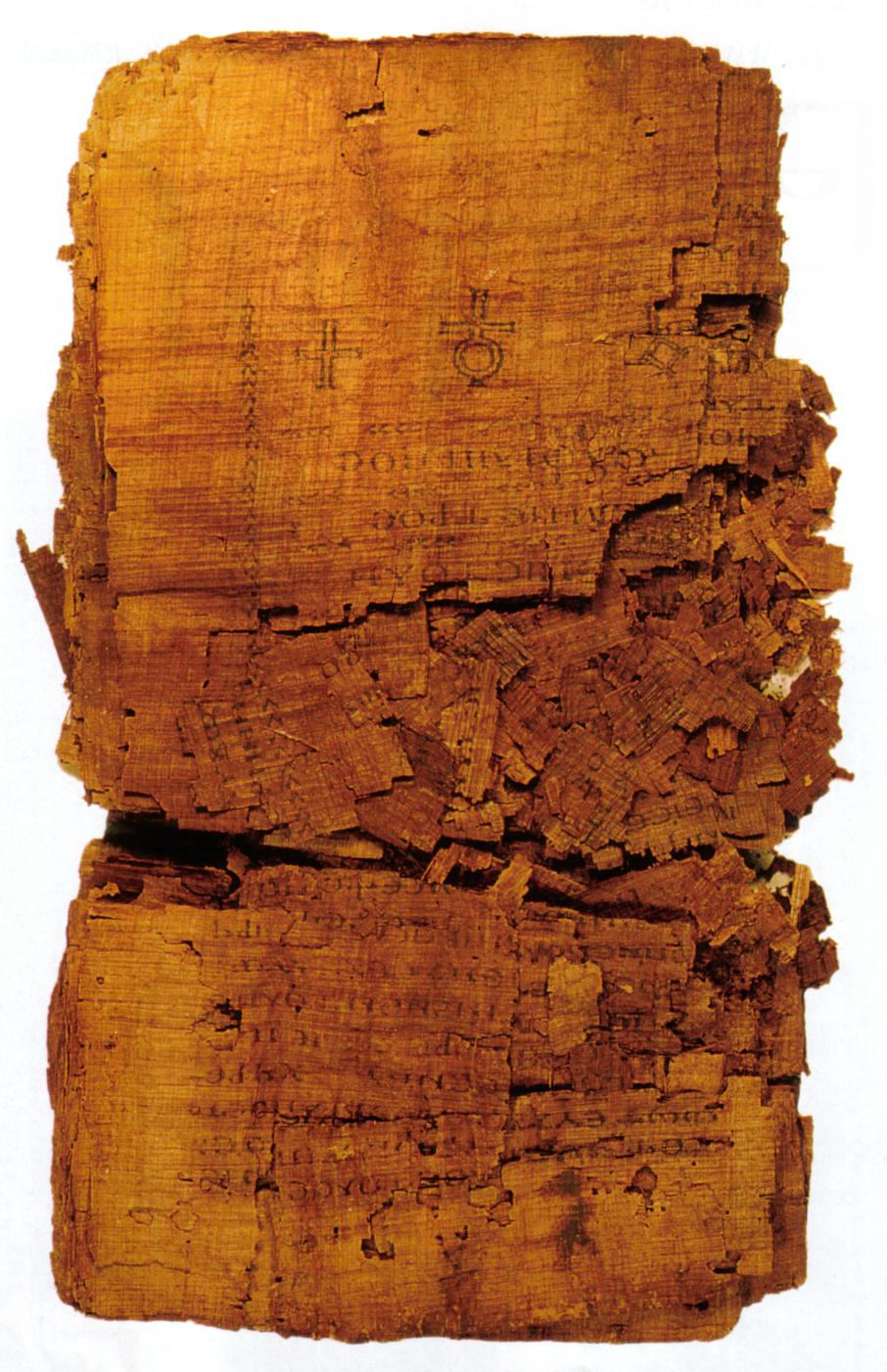

We began the class with a summary of the rediscovery of the literary sources for Manicheism and Mandaeism, noting the Manichean documents discovered in Turfan in the early twentieth century, the Cologne Mani Codex in 1970, and the Mandaean literature that began to appear in the late nineteenth century. Then we focused on Manicheism with some basic introductory material on the life of Mani, a description of the Manichean cosmogony, anthropology, social hierarchy, literature, and dispersion. I find the Cologne Mani Codex particularly interesting as an artifact because of its size—at 3.5 cm high and 2.5 cm wide it is one of the smallest books from the ancient world yet holds 23 lines to a page. I illustrated how little the codex is by having the class take out a 5, 10, or 20 dollar bill (this doesn’t work with loonies and toonies) …

The penultimate episode of CNN’s Finding Jesus: Faith, Fact, Forgery tells the story of the discovery of the True Cross by Helena, the mother of Constantine. Through a mixture of dramatic re-enactments, scholarly commentary, and relic-hunting sleuthery, viewers learn much about the life of Helena, her son Constantine, and the Christianization of the Roman Empire. But, as in previous episodes, the sources relating to the artifacts are not treated with the kind of critical rigor that they require. There are multiple versions of the inventio crucis, the discovery of the True Cross, not all of which even feature Helena, and they contain features that are fantastic (such as the method by which Helena determines which of the three crosses is Jesus’) and disturbing (they treat the Jews in the narrative as money-hungry, obstinate enemies of the church). Yet, the narrator of Finding Jesus more often calls the sources “tradition” and “church history,” and the finding of the cross is likened (both in the dramatizations and in the scholarly commentary) to an archeological dig. A 45-minute documentary cannot hope to present all of the nuances related to this topic, or any topic for that matter, but the episode would have benefited from some finer discussion of the sources, some of which are apocryphal texts.

The penultimate episode of CNN’s Finding Jesus: Faith, Fact, Forgery tells the story of the discovery of the True Cross by Helena, the mother of Constantine. Through a mixture of dramatic re-enactments, scholarly commentary, and relic-hunting sleuthery, viewers learn much about the life of Helena, her son Constantine, and the Christianization of the Roman Empire. But, as in previous episodes, the sources relating to the artifacts are not treated with the kind of critical rigor that they require. There are multiple versions of the inventio crucis, the discovery of the True Cross, not all of which even feature Helena, and they contain features that are fantastic (such as the method by which Helena determines which of the three crosses is Jesus’) and disturbing (they treat the Jews in the narrative as money-hungry, obstinate enemies of the church). Yet, the narrator of Finding Jesus more often calls the sources “tradition” and “church history,” and the finding of the cross is likened (both in the dramatizations and in the scholarly commentary) to an archeological dig. A 45-minute documentary cannot hope to present all of the nuances related to this topic, or any topic for that matter, but the episode would have benefited from some finer discussion of the sources, some of which are apocryphal texts.

The legend of the True Cross belongs to a genre of literature known as the inventio, each of which tell of the finding of relics associated with Jesus and other prominent first-century church figures. More …

The TA and Sessionals strike at York continues but some classes taught by full-time faculty have resumed, including my Gnosticism course. The few weeks off led to some confusion for me on the organization of the course (see below) but I was happy to be back in class.

We continued our journey through Nicola Denzey Lewis’ textbook, covering several more of her thematic chapters. This week we read the two chapters on apocalypses. Chapter 18 of the textbook focuses on texts with “apocalypse” in their titles (the Apocalypse of Adam and the Apocalypse of Paul, but not the Apocalypse of Peter and the two apocalypses of James, which are examined in other chapters) and chapter 19 focuses on Platonic Sethian Apocalypses (Zostrianos, Allogenes, and Marsanes). I made only passing mention of the Sethian texts in the lecture, in part because I discussed them in a previous class on the development of Sethianism, but also because they are difficult texts to read due to the damage in the codices, and because they really do not fit well the definition of the apocalypse genre, which states (from the Semeia definition), “‘Apocalypse’ is a genre of revelatory literature with a narrative framework, in which a revelation is mediated by an otherworldly being to a human recipient, disclosing a transcendent reality which is both temporal, insofar as it envisages eschatological salvation, and spatial insofar as it involves another, supernatural world.” The Sethian texts are identified as apocalypses by Porphyry …

The fourth episode of CNN’s Finding Jesus: Faith, Fact, Forgery examines the contentious ossuary of James, the brother of Jesus, which David Gibson (author of the companion book to the series) calls the “first physical evidence that Jesus of Nazareth existed” (I guess they are already discounting the Shroud of Turin from episode 1). The episode was fair and balanced in its presentation of the evidence for the authenticity of the ossuary and, to my delight, mentioned several apocryphal texts in its piecing together of James’ biography. It was also nice to see them open the episode with shots of the Toronto skyline for their introduction to the ossuary—the artifact made its debut at the Royal Ontario Museum in 2002, the only time it has been on display.

The episode is entitled “The Secret Brother of Jesus.” While the existence of James may be news to some Christians who do not read the Bible, it is certainly no secret. James is mentioned as one of four brothers, and two sisters, in Mark 6:3 and Matthew 13:55 and he features prominently in Acts and the letters of Paul, and of course is author of his own New Testament letter. But if Jesus’ mother Mary was a virgin, where did these siblings come from? Protestants have no issue with the idea that Mary had children with Joseph after the virginal birth of Jesus; but Roman Catholics do not take the Gospels’ mention of them as “brothers and sisters” literally and identify them …

I will be a guest on the Talk Gnosis webcast Wednesday, March 25. They will be asking me about the Secret Gospel of Mark. The show will be live on Youtube (at https://youtu.be/uoIhzYmsiFc) beginning at 9 pm EST and a more in-depth podcast will follow. You can check out past interviews at https://www.youtube.com/user/GnosticNYC.

This week’s episode of CNN’s six-part documentary series Finding Jesus: Faith, Fact, Forgery focused on a literary artifact: the Gospel of Judas. When the text was published in 2006 it caused quite a sensation. It’s initial editors declared that it portrayed Judas as a hero, not a villain. Scholars were cautious in their conclusions about the text, saying that it had no bearing on the historical Judas, but the media were not interested in what it revealed of second-century controversies—they wanted to know what it said about the life of Jesus.

This week’s episode of CNN’s six-part documentary series Finding Jesus: Faith, Fact, Forgery focused on a literary artifact: the Gospel of Judas. When the text was published in 2006 it caused quite a sensation. It’s initial editors declared that it portrayed Judas as a hero, not a villain. Scholars were cautious in their conclusions about the text, saying that it had no bearing on the historical Judas, but the media were not interested in what it revealed of second-century controversies—they wanted to know what it said about the life of Jesus.

The first half of the episode focuses on dramatizing the relationship between Jesus and Judas. Certainly he was one of the Twelve, the inner circle of Jesus’ followers, but perhaps producers went a bit too far in portraying the two men as intimate friends. Ben Witherington says, “Judas may well have been one of the very first he recruited”—sure, but we have no evidence of that. Other contributors declare Jesus and Judas close friends and state that Jesus was an excellent judge of character (I think the writer of the Gospel of Mark would disagree); one dramatization shows Jesus saving Judas from a fall.

The scene changes to the story of the woman who anoints Jesus. The producers focuse on the version of the tale from the Gospel of John (12:1-11), where Mary, the sister of Lazarus, is identified as the woman with the jar and Judas objects to the wasting of the expensive perfume. The story …

The latest episode of CNN’s Finding Jesus: Faith, Fact, Forgery, a mini-series which aims to present “fascinating new insights into the historical Jesus, utilizing the latest scientific techniques and archaeological research,” focused on relics of John the Baptist. The episode was a sequel of sorts to a 2012 National Geographic documentary called The Head of John the Baptist, which examines claims that a set of bones found in Bulgaria belonged to John (details HERE). CNN followed the efforts of experts to authenticate another relic of John from Kansas City but derived some of its content for the episode from the NGS production and even included commentary by Candida Moss, who was featured prominently in the early documentary.

The Bulgarian bones were discovered in 2010 among the ruins of a fifth-century church on the island of Sveti Ivan (“Saint John” in Bulgarian). They were found mixed together with animal bones in a marble reliquary beneath the church altar. No name is on the box, but a portion of a smaller box found nearby in an older part of the church bears an inscription that reads, “Lord hep your servant Thomas…of Saint John…in the month of June 24th.” The date is significant as it is the traditional date of John the Baptist’s birthday. One theory has it that this Thomas brought the bones to Bulgaria in the small box and they were subsequently moved to the larger box. Unfortunately, the Finding Jesus episode mentions nothing about the smaller box, …

Classes at my university (York in Toronto) have been suspended for the past week due to a strike by the teaching assistants and part-time instructors. Undaunted, I put together a Youtube video of my lecture so that the class could continue with relatively little disruption. The assigned readings from the textbook covered three topics: rituals relating to the Five Seals and death, martyrdom, and the Divine Feminine.

Ritual practices can be difficult to retrieve from texts. Consider, for example, Christian practices. A typical liturgy today contains various readings, prayers, responsories, and credal formulas derived from the New Testament (and sometimes the OT) but they were not intended to be used liturgically, so we could read these texts and not expect them to necessarily reflect early Christian practices. The Lord’s Prayer and the Eucharist are exceptions; both of these show signs that they were used in liturgy; so they have a liturgical existence both before and after the texts. What do we have in Gnosticism?

The Gospel of the Egyptians may be a handbook to Gnostic liturgy, specifically to the Five Seals ceremony. We have two other witnesses to this ceremony: the Trimorphic Protennoia and Irenaeus’ description of Valentinian (Marcosian) practice. My original goal of the class was to re-enact these three descriptions of the ceremony. We weren’t able to do that, so my Youtube video guided the students through the texts and considered what they may or may not tell us about the ceremony.

A hypothetical reconstruction of the complete …